It's okay to make money

Burn rates, smoke and mirrors, and building profitably

In 1970, Chicago economist, Eugene Fama, argued that information flows in public markets make it impossible to build a portfolio that consistently outperforms - information is “priced in.” The book Efficient Capital Markets went on to win Fama a Nobel prize and built the foundation of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). Most finance undergrads learn the legend of Fama on day one of Asset Pricing 101. However, on day one of Behavioral Finance 101, students are met with a direct criticism of Fama as Shiller spares no expense in tearing away at the EMH. Many (if they’re anything like myself) are left scratching their head questioning everything - Are markets priced in? Do investors actually act rationally? This debate over the EMH is best reserved for the sidewalks surrounding Harper Center and Wall Street, not Sand Hill Road and not the focus of this essay.

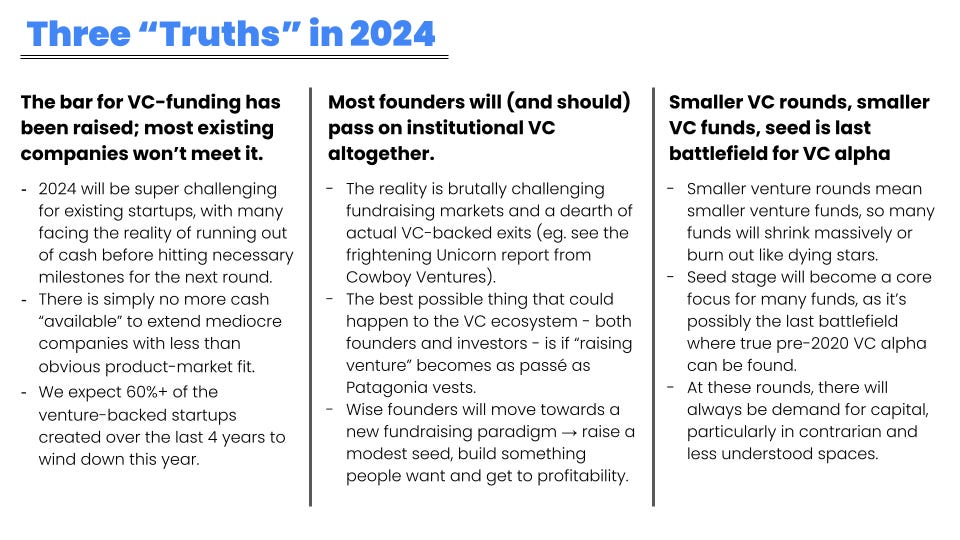

This being said, the criticisms that Fama saw in his work in the fields of finance and economics should also be applied to the nascent decalogue in start-up land. For most founders, Blitzscaling to capture and dominate the market in a globalized world is the bedrock that ideas are formed on, capital is raised on, and runway is burned on.

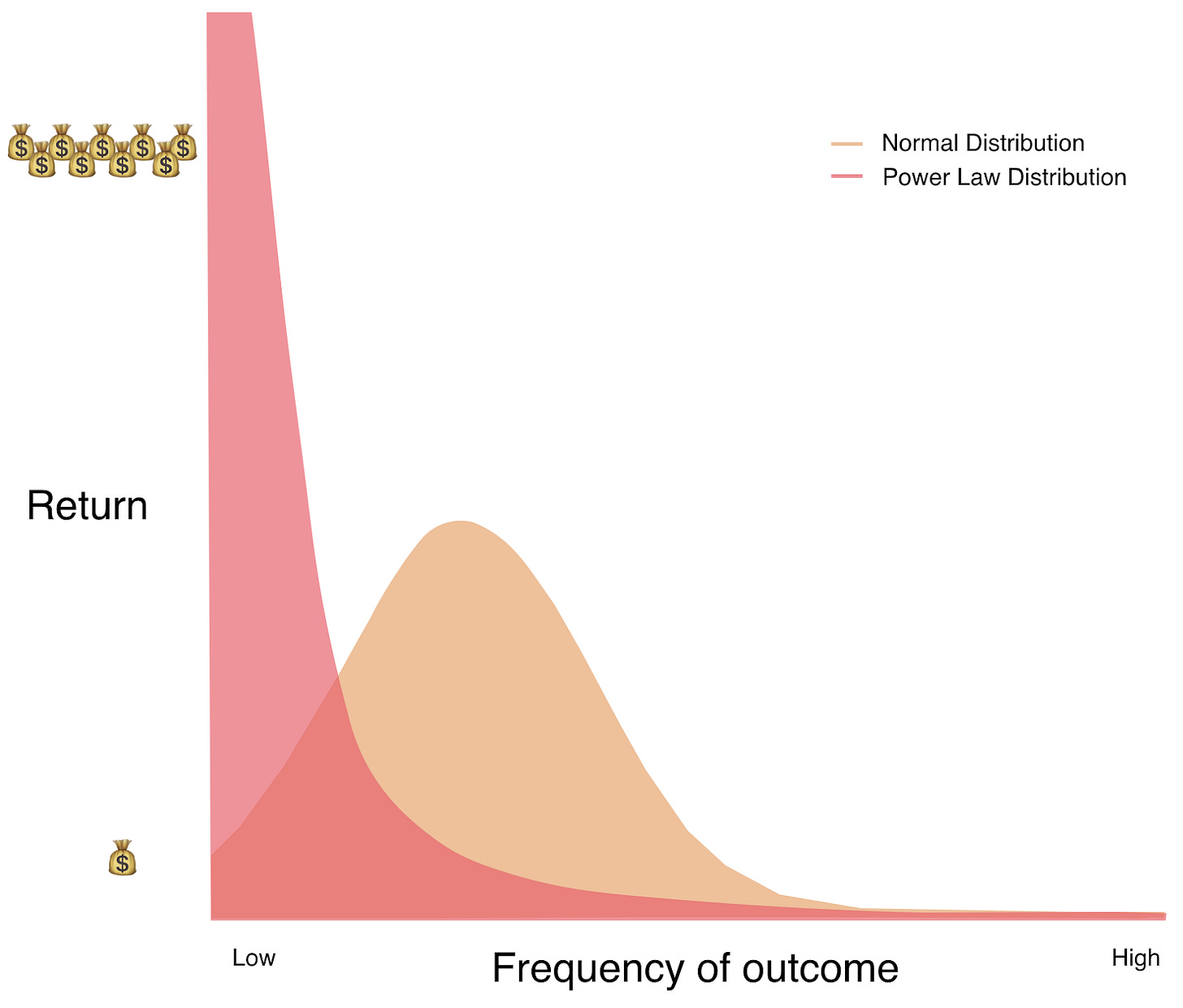

VCs have followed a framework that mirrored the thesis Fama attached to the markets: freer flows of information, transparency in pricing, and globalization don’t allow for easy alpha. Markets are efficient and rational, so you better start burning those dollars to dominate your TAM and make the world a better place. Following this framework for the better part of the last decade, venture backed bets have been the only noble pursuits in hallowed grounds of SoHo House happy hours and SXSW coffee-chats. And, from the buyside, the rapid scale playbook computes well. The asymmetry of venture portfolios supports power law incentives. From an investor’s perspective, it’s beyond necessary to have each PortCo go for the 10x bet. If 1 in 10 account for all the returns, you can’t afford a knock on IRR if your only winners are medium X’ers. This incentive structure means a natural push for founders to grow, grow, grow, at all costs. And, for the most part, founders have subscribed to the SV model of raise (dilute), spend, grow, repeat. There are a select few companies where this is the only way to capitalize: those that need immense network effects (Snap, Meta, Uber, etc) or technical intensity (SpaceX, Waymo) to back into immense asymmetry from a risk reward matrix.

But what about those medium X’ers? What about the the N’th SaaS or consumer utility app? Historically, the technical intensity of these products justified (to a degree) frothy rounds. But with rapidly decreasing CAPEX costs and abundance of cheap tech leverage, it’s clear more can be done with less - so why isn’t that reflected in how startups are capitalized?

In the current environment, the consensus is a lot of companies are walking dead. Many will say these companies failed to execute, find product market fit, or their founder was distracted shitposting on Twitter. But I’d argue that many of these failures are failures of balance sheet and cap table incentives. As Alex Danco put it, “The greatest trick VCs ever pulled was convincing founders, ‘you’re just like us.’” For the past decade of free money and good times rolling - the cycle supported deeply capitalized bets both financially through constant up-rounds and culturally through founder friendly tweetstorms. But what happens when rate driven austerity measures dry up capital and support for founders reaching for the stars? My mentor and dear friend, Alec Andronikov, said it best in his post My Biggest F-up of 2017: Chasing Shiny Innovation:

You have to remember: the vast majority of VCs are NOT in the game of innovation. They care about one thing and one thing only: maximizing their IRR in the shortest time possible by getting the highest valuation possible… They do NOT care about your personal struggles of making really crappy income while you are building value for them.

For the wide-eyed quixotic founder off a 2022 Series A extension, the take is crass and jaded. But, in a world where discount rates are nonzero, the Overton window shifts into making money and away from effective altruist shibboleths.

Maybe it’s the perspective from watching hundreds of companies spin tires and close rounds from less-than-ideal partners at sub-par terms that triggers my fight or flight. But does this mean that founders should pack up, discouraged and running with tails between their legs? No. It just means there’s a new game to play (and one that’s arguably more exciting). One that I’m playing: the Silicon Valley Small Business (SVSB). SVSBs pull the best of both worlds from SMBs and classic startups. From the SV side, retaining frameworks of infinite leverage and growth hacky creativity and from the SBs, day one profitability and rational spending habits (no, we don’t have Kombucha on tap).

But for those of you that are venture backed, the lessons learned from SMBs can still be applied without sacrificing growth (and no, this doesn’t mean you have to start using Teams and move your Chelsea office to Ding Dong Texas).

What I learned from working with small-town HVAC companies and widget manufacturers, is the intense bottom up evaluation of each cost-center. The constant conversation of “why are we paying Joe the PVC pipe guy that?” “let’s tell Xfinity we’re moving to CenturyLink” etc. However, the SV of the SB here is SMBs will sacrifice growth for profitability, failing to put dollars on testing and innovation. Why? Not only because growth is physically localized, but because those are balance sheet dollars. Meaning, if you’re operating at 20% EBITDA, you pad the balance sheet to prep for the next inevitable Silverado and technician.

But, by the miracle of $0 marginal cost with software, net profit margins climb to comfortable ranges where you can then predictably set aside exploratory dollars on channel testing → substituting CAPEX for CAC, setting B/E hurdles, and timelines for those exploratory dollars to become profitable or call it quits.

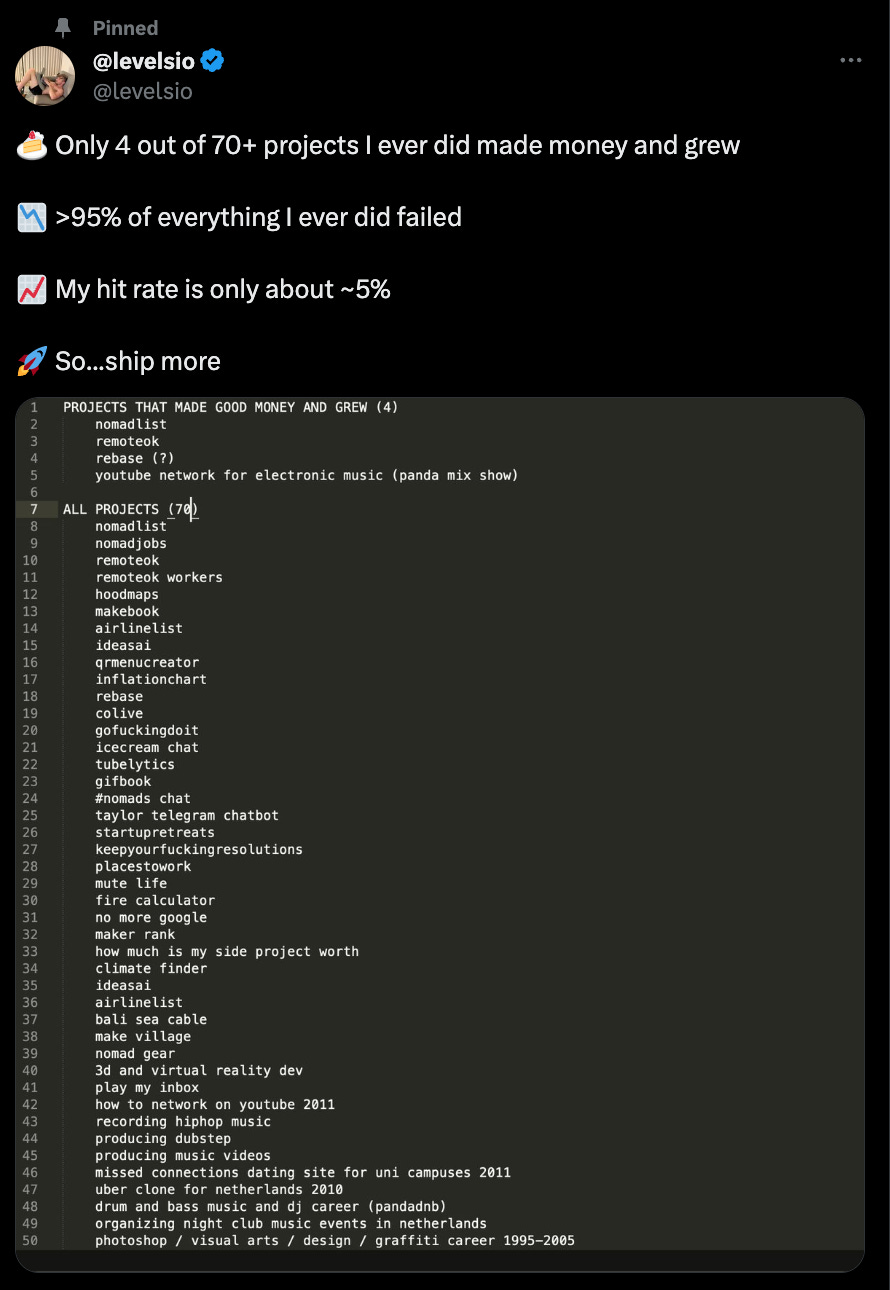

This structure is the inevitable future of tech. Small teams (sometimes individuals such as @Levelsio) who are aggressively throwing projects to users, iterating quickly, pulling the plug on losers, and running it back.

Will there be a place for venture dollars? Sure. But it won’t (and shouldn’t) be like the free ZIRP dollars of the last decade. This might be obvious for some, but for most there’s a thing or two to learn from the mom & pop SMB in the Deep South or Midwest.

My shameless plug here is this unit economic focused building is central what we’re helping companies solve here for at NewForm; we’re rapidly opening up our clients to growth frontiers with profitability on an agency level. Where, instead of thinking of the next VC coffee chat, founders will be able to think about recycling profitable dollars back into growth - preserving dilution, control, and (hopefully) sanity over the lifecycle of their business.

And no, we’re not doing this because we’re nice generous people. It’s because when shit hits the fan and our clients realize we’re making them real money, we’ll be just fine, and they’ll keep helping us help them make the world a better place.

Want to chat? Feel free to grab some time here.

This is a very thoughtful breakdown, and I totally agree

Biased here--but totally agree. There's been a shift in the Overton window here in silicon valley, and suddenly it's cool to be building boring (profitable) businesses. Not every business is a VC business, and most money is clearly made outside the confines of VC